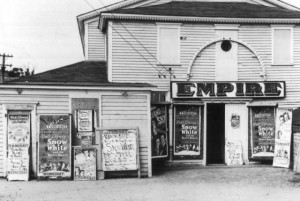

The Empire Theatre ca. 1882: The rollerskating rink/summer theater looks out on the intersection of High Street, Spring Street and Water Street. The statue of Rebecca was not erected until 1896.

They came ashore with the paraphernalia of their journey, looking to Block Island for respite and a bit of refreshment after the sea voyage. Their destination was the site of the Empire Theatre, where also perhaps, as a bonus to their main purpose, entertainment might be found meeting the quaint local people, so rooted on their isolated island.

These were not tourists with shopping bags and decorated T-shirts — these men carried muskets and swords. They were the empire — the British Empire — and they meant to preserve its mighty reign over the oceans of the earth. But first they needed to quench their thirst.

It was the War of 1812, and the new United States was fighting England for free use of the sea. Isolated Block Island could afford only to be neutral, and so British sailors often came to a tiny cove along the eastern shore to fill their water casks from a large shoreside pond. We call that spot Old Harbor.

The Empire Theatre in 1949: The sign for “Bowling” points to the bowling alley behind the theater, which was renovated in the 1980s to become the Seacrest Inn.

In 1882, 70 years later at that site, during the midst of Old Harbor’s frenetic building boom, the Empire Theatre was built as a roller-skating rink. By that time, the pond’s edge had been eroded by the sea, and the remaining wetland filled in by islanders — although the stream that fed the pond still flows down between High Street and Spring Street, disappearing now in the swamp near their juncture.

For most of the past 111 years, the Empire has presided over the hub of Block Island, providing refreshment and entertainment for a new wave of usually neutral invaders.

But at the height of the island’s recent popularity, the theater was inexplicably closed at the end of the 1986 season. It was a victim of Rhode Island’s main product during the late 1980s: political, real estate and banking fraud. The space in newspapers formerly used for movie advertisements was replaced with photographs and stories of the theater’s mainland owner, alleged to be one of the state’s 10 worst offenders in the widespread scandal — the same developer who turned Peckham Farm, next to Rodman’s Hollow, into a housing subdivision and enlarged the unobtrusive Cutting Cottages on Corn Neck Road.

During the next few years, several prospective purchasers of the Empire Theatre put forth plans to turn the site into a shopping mall, even an underground parking garage was proposed (with a large water pump, no doubt).

But — just as in a movie — Block Island experienced a real-life “Return Of The Empire” in 1992, when new owner Gary Pollard vowed to save the original building and reopen the theater. The new — or rather “newer” — padded seats still rest on the original hard pine floor, built with raised ramps along the side for skaters to roll back to their seats.

In August 1882 the inaugural opening was noted by Providence newspapers:

“The new rink has only been used once prior to last Saturday evening, which was chosen by the proprietors as the time for the formal opening under the management of Prof. F. L. Harrington, of Providence. An orchestra of eight pieces from Hartford furnished music, and Prof. and Mrs. Harrington gave some fine exhibitions of fancy skating. The attendance was very good in view of the fact that the entertainment has not been very generally advertised. A similar exhibition, with skating by the public, will be given on next Tuesday evening, and a game of polo on skates will be played next Thursday evening by the Providence Blues and The Block Island Reds.”

The game of “polo on skates” was a form of ice hockey, whose rules had just been formalized by Canadians in 1879. As Block Island’s bustling hotels were enlarged yearly in the 1880s, the skating rink remained a favorite, as in the summer of 1884:

The Empire Theatre in 1937: In 1937 Walt Disney’s first full-length animated movie, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” was well-publicized at the Empire.

“On Thursday evening, the skating rink was decorated with the nineteen flags of the international code, and lanterns in profusion. Professor Edwin Dennis gave a fine exhibition of aerobatic and fancy skating, after which the skating became public, and 150 skaters surged upon the floor, continuing the exercise until half-past ten, to the music of the National Orchestra of seven pieces, from Haverhill, Mass.”

By the late 1880s, the building’s owner — Block Island resident Cassius Clay Ball (1854-1925); known, understandably, as “C.C.” to everyone — changed the rink to a summer theater, providing dancing classes, masquerade balls, and vaudevillian works until 1905 when the use reverted briefly to a roller-skating rink.

That nearly 100-year-old canvas banner — 30 feet of carefully hand-painted lettering proclaiming “2 hours FUN for 30 cts” — was found under the old stage by Gary Pollard during exploration of the theater’s hidden areas, and now hangs inside on the wall opposite the movie screen. Other theater mementos — visible nourishment for the island’s love affair with its past — are displayed in the enlarged lobby.

About 1910, movies were shown on a regular basis — during the great “silent era” — and the building was for the first time called the Empire Theatre.

In 1913, the theater even produced a song, a four-page piece of sheet music titled “I’d Rather Be At Block Island Than Any Place I Know,” written by James Tammany. The gist, universal appeal, and faultless logic of the lyrics can be appreciated in the opening line: “Summer’s the time that we all like best cause vacation time is here.”

The Empire persevered through the Roaring ’20s, the Depression ’30s (when movies were needed most), and the relaxed poverty of the ’50s.

From the 1960s into the 1980s, under the able ownership of King Odell, shows were held twice nightly at 7 p.m. and 9 p.m., with titles remaining the same for two successive nights — except for Thursday, when the movies were one-night stands aimed at the younger kids. No one minded, in that age before video rental stores made reruns easy to see, that the movies were usually six months to a year old.

The frequently changing schedule plus the $1 ticket price (50 cents for children, dogs free) encouraged movie going without much thinking — just as it should be. If you didn’t know what was playing, you went anyway, the expectancy of the event usually outweighing the reality of even the worst movie titles. In fact, the decision to go or not — for the youthful anyway — depended more upon who was in line along the sidewalk, or who could be enticed from the road as their car circled Water Street for the eighth time that night.

But what counted most for everyone was simply that when the marquee lights of the Empire returned, summer was back. Or, as the 1913 song says about Block Island: “The bathing is fine and you’ll have a good time at the Moving Picture Show.”

“Cinema Paradiso” is the story of a classic small-town movie theater that played an oversized role in knitting a small Italian community together. The Empire Theatre has performed a similar role on Block Island for most of its 131 years.

“Cinema Paradiso” is the story of a classic small-town movie theater that played an oversized role in knitting a small Italian community together. The Empire Theatre has performed a similar role on Block Island for most of its 131 years.